Thanks to health outreach groundwork laid prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, farm worker communities across Vermont had access to on-site vaccine clinics through a partnership between UVM Extension, the Vermont Department of Health, UVM College of Nursing and Health Sciences, UVM Larner College of Medicine and UVM Medical Center.

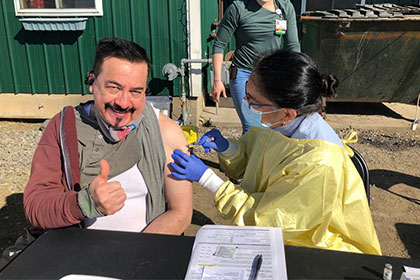

A farm worker receives a COVID-19 vaccination from Nelly Aranibar-Salomon, UVM Extension community outreach nurse. (Photo courtesy of UVM Extension.)

In early June, UVM Extension announced that it had received a $224,178 grant for vaccine education efforts for Vermont’s migrant and seasonal farm workers, especially those in Bennington, Caledonia, Essex, Franklin, Orleans, Windham and Windsor Counties.

The funding provides needed support for adult immunization among farm workers—not just for COVID but for other public health threats. Projects will be led by Naomi Wolcott-MacCausland, migrant health coordinator for UVM Extension's Bridges to Health program, and Sarah Kleinman, director of 4-H and UVM Extension family and farmworker education programs, along with a team of Extension colleagues.

The larger story is how the groundwork for expanded outreach was laid in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple partners, including UVM Extension, the Vermont Department of Health (VDOH), UVM College of Nursing and Health Sciences, UVM Larner College of Medicine and the UVM Medical Center, worked together to get shots into arms of vulnerable farmworker populations.

Weighing the Risks

Early in the pandemic, the national Extension system formed partnerships with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to acquire funding for vaccination education across the country.

Dan Lerner, Extension associate director, brought together colleagues to discuss how to use this initial funding to distribute CDC “vaccinate with confidence” materials in Vermont. The publications encourage readers to get vaccinated while addressing barriers including hesitancy and misinformation. The team was also asked to identify target populations for the information campaign.

“The funding is meant for underserved populations including hard to reach rural populations and BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Color] people, so it made sense for us to continue our work with farmworkers in the state,” said Kleinman.

Overlaying the CDC’s social vulnerability index with what Extension professionals already know about the state farmworker population, the team was able to identify specific counties and farm locations where local support systems like free clinics were especially lean.

“We’ve been doing health outreach on farms since 2010,” notes Wolcott-MacCausland. “And that built on outreach going on over the last few decades through the Vermont Migrant Education Program. So there have been people in Extension visiting farms that outsource labor across the state for many, many years.”

She explains Vermont’s migrant farm labor force is largely comprised of Latino migrant farmworkers, many who work in the state’s dairy industry, and short-term seasonal workers on agricultural visas, mostly from Jamaica, who harvest fruit and ground crops.

Both groups hit all the checkboxes for population vulnerability.

They are categorized as essential laborers who live and work in close proximity with each other. Long work hours, on-site housing, lack of reliable transportation and for many, limited English skills, means public information campaigns about the importance of flu shots or COVID-19 safety protocols likely won’t reach them. Many are undocumented workers and don’t qualify for health insurance. Seasonal workers on visas are not eligible for Medicaid and plans through the health exchange are cost prohibitive. As a result, they are more likely not to seek preventative care.

UVM Extension works mostly with farms located in remote, lightly-populated parts of the state like northwestern Vermont and the Northeast Kingdom where there are no free clinics, and where existing community health centers and hospitals struggle to meet the linguistic and cultural needs of migrant workers. Addison County, which has a large and concentrated population of year-round dairy workers and seasonal crops workers, has access to the Open Door Clinic, a free clinic funded by a mix of state funds, grants and philanthropy.

The Importance of Partnerships

Late last summer, Wolcott-MacCausland and her colleagues began hearing media messages about how important it was to get a flu shot—and how simple it was to get one.

“We were saying to each other, ‘Hmm, it's actually not as easy as you think for some people,” she said.

She also knew that the COVID-19 vaccine would be ready sometime in 2021 and the state had to be prepared with a distribution plan for farm workers. With limited time and funding, the solutions would have to be creative and nimble.

She brainstormed with Benjamin Clements, M.D., a family physician at the UVM Medical Center and assistant professor of family medicine at the Larner College of Medicine. Clements found some funding through a Vermont Medical Society grant to put together the Latino Migrant Farmers Flu Clinic Team. Wolcott-MacCausland and two bilingual registered nurses funded by the Vermont Department of Health coordinated farm visits to perform COVID prevention education. They were joined by Clements, who secured access to the flu vaccines and volunteer medical students travelling to farms throughout Vermont Northern and Central Vermont.

The group visited 56 farms across eight counties, providing flu vaccines to 261 migrant and seasonal workers as well as local workers and farm owners. A collaboration with The Health Center in Plainfield and the Windham County Department of Health supported additional access to 35 more workers on six additional farms.

In a health care system overwhelmed with COVID-19 cases, a broader-based flu shot effort seemed like a bridge too far, but the process provided a road map for future COVID vaccination efforts.

As testing and contact tracing efforts stepped up statewide, the Vermont Department of Health continued to be a key collaborator. In early 2021, the department funded UVM Extension to set up mobile testing and increase staffing to bring COVID tests to the farms.

“The Department of Health has really stepped up a health equity initiative as a result of COVID,” said Kleinman. “They are looking to the future to figure out how to address health inequities across many different vulnerable populations.”

UVM Extension was deeply involved in education and testing when new vaccines began to roll out this spring. Given how rapidly events unfolded, some field visits by Wolcott-MacCausland’s team included education, testing and vaccination simultaneously. The final documented case was diagnosed in the last week of March and vaccination began around the 6th of April.

“In one case we had planned a second-dose clinic on a farm when the farm owner contacted us to say he had a new incoming worker,” she recalls. “If we're going to a place to test, then we’ll also answer questions about vaccines for people who are reluctant to get vaccinated.”

One worker was on the fence about being vaccinated. He chatted quietly with a Spanish-speaking practitioner for about 15 minutes.

“Right as we were packing up to go, he came up and said ‘OK I’m going to go for it,’” Wolcott-MacCausland said. “If he had said ‘no’ and then two weeks later said ‘yes,’ then we would have figured out how to get him the shot one way or the other.”

Being flexible was the order of the day.

Conversations with farm workers often led to debunking misinformation. One worker showed practitioners a video of a Spanish-speaking man claiming that vaccination placed a magnetized microchip in the arm. Allowing workers to inspect the syringes and vaccine vials and demonstrating that magnets weren’t attracted to arms of vaccination recipients often convinced them that vaccination was safe.

Wolcott-MacCausland estimates that 21 people who initially declined vaccination eventually decided to get their COVID-19 shots.

Health Threats and Equity

While the COVID-19 pandemic may soon be history, collaborations forged during some of the darkest moments over the past year have built an infrastructure to handle future crises and provide greater trust in vaccination and primary prevention.

As of June 15, 749 migrant and seasonal farmworkers, owners and local workers at 92 farms have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. The work is ongoing.

The recent funding from the Extension Foundation was provided through the Extension Collaborative on Immunization Teaching and Engagement (EXCITE) immunization education program. EXCITE funds will also support UVM Extension launch educational campaigns in Spanish and English to share COVID-19 resources and other adult immunizations.

On a more basic level, says Wolcott-MacCausland, it brings to light the dramatic inequities in access to health care in Vermont.

“These disparities have existed on local farms for a long time—it didn’t start with COVID and won’t end with COVID. I’m hopeful that the public attention and this new funding will help us make continual progress.”

In addition to critical funding from VDOH, key partners in this effort have included the VDOH Health Equity Team, Northern Tier Center for Health, Dr. Clements through UVM Medical Center, VDOH district offices around the state, Newport Ambulance Services, Waterbury Ambulance Service, Windham County Rescue Inc, and BIPOC-focused community clinics.